A Rainbow in Hades

A college trip to Boston, New York, and Philly. See friends. A mother-son trip, our first and perhaps last. For him, New York was to be the highlight.Carter asks to go to the 9/11 Museum, a trip I dread, but if my kid wants to go, I will go with him. I make an appointment and am told we will have use of a family room if we need some time to ourselves. Perhaps seeing the museum through a 16-year-old's eyes, who I assume is less emotionally attached given he was a two-year-old when the event occurred, will be easier. But it will not be easy.At six, Carter built a cardboard model of the towers. He knew their height, which floors of the towers the planes hit, how many people were killed, minute technical details. The night before his first-grade "show and tell" presentation, I made him promise not to show the Time Life magazine's more graphic pictures to his class.His learning about the event seemed as emotional for him as learning about volcanoes or dinosaurs. He learned facts. He loved gory details. He did his show and tell and I rarely heard about 9/11 again. He no longer needed to pour over that ghastly book.The afternoon before our visit to the museum, we noodle around Times Square, jostling along with the hordes of people, noting that the Naked Cowboy is still there (is he the same guy as 15 years ago?). We are hustled by the guys "giving" us their Hip Hop CD demos for a small "donation." They flatter and cajole over what are probably blank CDs. Finally, we escape the mayhem and find a quiet Indian restaurant on the second floor of a building on 49th or so."I don't think I like New York as much as I thought I would," he says. "It's cool and stuff, but all that consumerism and greed. It's so in your face." I agree that Times Square is certainly a good example of greed. "It's weird to be here," he says. "I mean, it's New York, and that's exciting, but it's also where Daddy died."I too feel uneasy in New York. I always have. Its over-the-top tallness, crushes of people, blatant displays of both wealth and poverty. In just over an hour, we are both on edge, feeling a strange, jittery unease."After we do the museum tomorrow, we can go to some other areas that are a little more tame. A little nicer. Not so consumeristic," I say. I picture walking along the tree-lined streets of Greenwich Village or sitting in a nice outdoor cafe in Soho watching people walk by.We carry on our short tour, avoiding Times Square by walking through Rockafeller Center, down 5th to 41st and ducking back into the Port Authority to make our way to Montclair to see friends.The next morning, I wake Carter early and we say goodbye to our friends in their driveway. He looks pale, but I assume it is the early morning awakening. We pull out and drive 100 feet down the road when he starts to heave. He flings open the car door and is sick.This is not new. Usually, it happens on the way to airports. I spent many flights next to him, holding open the garbage bag that I had nabbed from a hotel or airport washroom as he threw up, rubbing his back, every half hour until we arrived home. We nearly spent one Christmas in an Atlanta hotel when the flight crew wouldn't let us board. That was the year I learned Olivia's ability to stand her ground, no matter who was in her way. I credited her for getting us on that flight.The significance of his episodes always happening before a flight only dawned on me years after they began when he was finally able to articulate that he was afraid of flying because he thought bad guys could get onto the plane and fly it into a building."Should we go back?" I ask him. I know we probably should. This isn't likely to end soon."I ate a bad Philly Cheesesteak last night," he says. "I'll be OK."This too has happened. A one-time deal, where he gets out whatever doesn't agree with him and carries on. I put the car in drive and continue driving. At the Port Authority parking lot, I slow the car and the door flings open again.I should turn around and go back to New Jersey, but I still hope for him to have his fun day in New York City.We get off the subway at the World Trade Center (previously called Chambers Street, I realize). He stops to barf into a trash bin. On the street, we follow the crowds down Vesey Street. He slows into a blocked corner, cordoning off ongoing construction. I leave him there to find Dramamine and return to find him sitting on the sidewalk away from the splatter. I hope the first dose works quickly. I picture the museum's family room having a couch and running water and make it our destination.At the museum, I find the "family" ticket window. We are directed to stand in line. Lines are not good. I feel around my purse for the plastic bag I begged from a subway Hudson News. I panic seeing the airport-like security screening. Counting back the minutes from the last episode, I estimate we have 15 minutes before the next.I am shocked by the number of people filing into the museum with us. It seems ghoulish. Why do they come? Why is this now one of the major tourist attractions in New York? I assume it's for the same reason people used to watch public hangings or rubber neck at highway accidents. But what is the curiosity about? Affirmation that it couldn't happen to them?I see a giant steel girder. We are really here. The few times I have been to the site, I have been conscious of being in the place where Arron died. I feel as if I am stepping on his body, as irrational as that is. My heart pounds.I get us to the cafe on the second floor and put Carter in a seat. He rests his head on the table. I buy water, give him another dose of medicine. I notice a woman, a security officer looking at us. I approach a docent, who oddly, doesn't know where the family room is located. He asks the security officer who has been watching us. I explain our situation to her. At first, she is all business and asks to see my ticket. She walks up to Carter, who is still resting his head on the table."You're not feeling well?"He shakes his head and looks up at her."Follow me," she says so abruptly that I scramble to collect bags and coats and she is standing by a door holding it open as I scurry after them.We are led into a room where I am relieved to see a couch and two chairs. Carter flops into one. I hunt around for a garbage pail. The security guard pulls out a large container from under a sink in the corner. Within a few minutes, Carter is heaving into it.When he is done, the security guard, who I have now learned is named Maria, leaves to get me tea.He begins to sob. I hold him close, something I realize I haven't done in a while. What 16-year-old boy wants comfort from his mom? I let him sob until he is spent. We let go and he flops back in his seat, looks around."This room is creepy," he says. The walls are covered with photos of loved ones, etchings of names from the memorial, children's drawings, prayer cards, things that family members have brought to add to the walls. This strikes me as odd. Who are they for? The other family members who come to this room? Is leaving a piece of their loved on in this room comforting in some way? Happy people smile at us - a guy on a bike, a young woman in the prime of life, another whose portrait is somehow haunting - she is gaunt with large, worried eyes. Did she subconsciously know her fate as I believed Arron did?Through obscured windows, painted with a dotted pattern, I see the crowds lingering around the South Tower memorial. The waterfall from inside the huge box falls into a pool with a square hole at its center, and water pours further down the abyss.The throwing up continues. Maria sits on the edge of one of the chairs and I learn a little about her. She worked in the medical field. Her brother died in 9/11 and her son convinced her to take the museum security job where she has learned to leave her emotions at work because every day she encounters another heartbreak.She tells of trying to help a young man, sobbing in front of one of the displays, a group of drawings of the Twin Towers made by traumatized area school children. He was with several friends, who were clearly uncomfortable with his display of emotion. She asked him if he had lost a family member but he shook his head. He pointed to one of the drawings. "I drew that in 5th grade," he said. We both had tears in our eyes.Maria also tells of the many wonderful things she sees every day. The humanity, the compassion. She is reminded of the strength of the city and it's people on a daily basis, is humbled by the thousands of people who visit the museum every day, to pay their respects, learn, understand. I begin to see the crowds as less ghoulish and more compassionate.Later, Carter finds his way to the couch and sleeps. I eat a sandwich. Another security guard offers to take me to the wall to see Arron's name. Maria insists I go while she stays with Carter.I learn that Bobby, my escort, is a retired New York City Police officer. He took the job for many of the same reasons as Maria. "I lost 30 friends and colleagues that day," he says. "It's my way of giving back." I wonder how many on staff at the museum work for this same reason. A form of healing, assuaging the survivor's guilt that so many survivors must feel.We find our way to Arron's section, N21. Almost 22, our shared birthdate. His name is centered between the two people who joined him at the conference that morning. The two people he hired only weeks before. It is strange to stand there, looking into an acre-sized square hole filled with water, a giant grave. The impossibility of it all hits me again. Bobby explains how people are surprised by how far apart the two buildings actually were. "People assume they were very close since it looks that way on TV," he says.Carter is still sleeping when I return and Maria asks if I want to go downstairs. I have been glad to have Carter as an excuse not to go. "My boss will accompany you," she says gently. I am torn. I don't want to go, but feel I should, somehow. Am I strong enough? Is there any benefit? I wanted to see the museum with Carter, not a stranger, even a very kind stranger. Maria gently pushes me and I agree to go.My new escort Claudio is a retired NYPD Lieutenant. He drove to Ground Zero that morning, positioned at the head of his fleet of motorcycles and commandeered hundreds of busses to evacuate people from the area. He didn't stop working for 42 days. We descend into the gloom and he points out things as we walk quickly past them, ducking in front of people gazing at the displays. Much of the info I already know, and we breeze along so quickly, I don't look closely at much. The pit under the North Tower memorial I remember from the one-year anniversary when we were corraled down the ramp into it. The slurry wall is like a vast sculpture with its giant bolts poking from it in regular intervals. Claudio tells me that during hurricane Sandy, the pit filled with 9 feet of water. "You can see the watermark there, on the steel girder. That was the last one they extricated from the site." The girder is covered in flags and graffiti and names, the lower ones blurred where they had been underwater. The amount of water that must have flooded the area is unfathomable.Claudio shows me how to find Arron's name on a touchscreen, and make it appear in the small theater nearby. I am sorry that I have never recorded something to go along with Arron's profile. I wish there are other photos of him as well, but at the time they were collecting such things, I wanted nothing to do with this place. I didn't want Arron there either. Now it seems a shame.I am fascinated by the display of the time lapse radar imaging of all the US flights that day. At 8am, the little yellow planes that scurry around the US map look like a swarm of bees slowly dying as the lapse continues through the day and the planes are grounded.Claudio's stops by a display showing the view of the burning towers from the space station which just happened to be flying over New York at the time of the attack. Even on satellite, it's possible to see the billows of smoke. He shakes his head, "they just happened to be flying right over at exactly that time," he says. "What were the chances of that?"On our way out, we pass a huge photo of one of the towers taken from someone standing on the ground looking up. Although the display is below ground, sunlight from a window above casts a prism of rainbow on it, that lines up perfectly with the angle of the side of the building.

A college trip to Boston, New York, and Philly. See friends. A mother-son trip, our first and perhaps last. For him, New York was to be the highlight.Carter asks to go to the 9/11 Museum, a trip I dread, but if my kid wants to go, I will go with him. I make an appointment and am told we will have use of a family room if we need some time to ourselves. Perhaps seeing the museum through a 16-year-old's eyes, who I assume is less emotionally attached given he was a two-year-old when the event occurred, will be easier. But it will not be easy.At six, Carter built a cardboard model of the towers. He knew their height, which floors of the towers the planes hit, how many people were killed, minute technical details. The night before his first-grade "show and tell" presentation, I made him promise not to show the Time Life magazine's more graphic pictures to his class.His learning about the event seemed as emotional for him as learning about volcanoes or dinosaurs. He learned facts. He loved gory details. He did his show and tell and I rarely heard about 9/11 again. He no longer needed to pour over that ghastly book.The afternoon before our visit to the museum, we noodle around Times Square, jostling along with the hordes of people, noting that the Naked Cowboy is still there (is he the same guy as 15 years ago?). We are hustled by the guys "giving" us their Hip Hop CD demos for a small "donation." They flatter and cajole over what are probably blank CDs. Finally, we escape the mayhem and find a quiet Indian restaurant on the second floor of a building on 49th or so."I don't think I like New York as much as I thought I would," he says. "It's cool and stuff, but all that consumerism and greed. It's so in your face." I agree that Times Square is certainly a good example of greed. "It's weird to be here," he says. "I mean, it's New York, and that's exciting, but it's also where Daddy died."I too feel uneasy in New York. I always have. Its over-the-top tallness, crushes of people, blatant displays of both wealth and poverty. In just over an hour, we are both on edge, feeling a strange, jittery unease."After we do the museum tomorrow, we can go to some other areas that are a little more tame. A little nicer. Not so consumeristic," I say. I picture walking along the tree-lined streets of Greenwich Village or sitting in a nice outdoor cafe in Soho watching people walk by.We carry on our short tour, avoiding Times Square by walking through Rockafeller Center, down 5th to 41st and ducking back into the Port Authority to make our way to Montclair to see friends.The next morning, I wake Carter early and we say goodbye to our friends in their driveway. He looks pale, but I assume it is the early morning awakening. We pull out and drive 100 feet down the road when he starts to heave. He flings open the car door and is sick.This is not new. Usually, it happens on the way to airports. I spent many flights next to him, holding open the garbage bag that I had nabbed from a hotel or airport washroom as he threw up, rubbing his back, every half hour until we arrived home. We nearly spent one Christmas in an Atlanta hotel when the flight crew wouldn't let us board. That was the year I learned Olivia's ability to stand her ground, no matter who was in her way. I credited her for getting us on that flight.The significance of his episodes always happening before a flight only dawned on me years after they began when he was finally able to articulate that he was afraid of flying because he thought bad guys could get onto the plane and fly it into a building."Should we go back?" I ask him. I know we probably should. This isn't likely to end soon."I ate a bad Philly Cheesesteak last night," he says. "I'll be OK."This too has happened. A one-time deal, where he gets out whatever doesn't agree with him and carries on. I put the car in drive and continue driving. At the Port Authority parking lot, I slow the car and the door flings open again.I should turn around and go back to New Jersey, but I still hope for him to have his fun day in New York City.We get off the subway at the World Trade Center (previously called Chambers Street, I realize). He stops to barf into a trash bin. On the street, we follow the crowds down Vesey Street. He slows into a blocked corner, cordoning off ongoing construction. I leave him there to find Dramamine and return to find him sitting on the sidewalk away from the splatter. I hope the first dose works quickly. I picture the museum's family room having a couch and running water and make it our destination.At the museum, I find the "family" ticket window. We are directed to stand in line. Lines are not good. I feel around my purse for the plastic bag I begged from a subway Hudson News. I panic seeing the airport-like security screening. Counting back the minutes from the last episode, I estimate we have 15 minutes before the next.I am shocked by the number of people filing into the museum with us. It seems ghoulish. Why do they come? Why is this now one of the major tourist attractions in New York? I assume it's for the same reason people used to watch public hangings or rubber neck at highway accidents. But what is the curiosity about? Affirmation that it couldn't happen to them?I see a giant steel girder. We are really here. The few times I have been to the site, I have been conscious of being in the place where Arron died. I feel as if I am stepping on his body, as irrational as that is. My heart pounds.I get us to the cafe on the second floor and put Carter in a seat. He rests his head on the table. I buy water, give him another dose of medicine. I notice a woman, a security officer looking at us. I approach a docent, who oddly, doesn't know where the family room is located. He asks the security officer who has been watching us. I explain our situation to her. At first, she is all business and asks to see my ticket. She walks up to Carter, who is still resting his head on the table."You're not feeling well?"He shakes his head and looks up at her."Follow me," she says so abruptly that I scramble to collect bags and coats and she is standing by a door holding it open as I scurry after them.We are led into a room where I am relieved to see a couch and two chairs. Carter flops into one. I hunt around for a garbage pail. The security guard pulls out a large container from under a sink in the corner. Within a few minutes, Carter is heaving into it.When he is done, the security guard, who I have now learned is named Maria, leaves to get me tea.He begins to sob. I hold him close, something I realize I haven't done in a while. What 16-year-old boy wants comfort from his mom? I let him sob until he is spent. We let go and he flops back in his seat, looks around."This room is creepy," he says. The walls are covered with photos of loved ones, etchings of names from the memorial, children's drawings, prayer cards, things that family members have brought to add to the walls. This strikes me as odd. Who are they for? The other family members who come to this room? Is leaving a piece of their loved on in this room comforting in some way? Happy people smile at us - a guy on a bike, a young woman in the prime of life, another whose portrait is somehow haunting - she is gaunt with large, worried eyes. Did she subconsciously know her fate as I believed Arron did?Through obscured windows, painted with a dotted pattern, I see the crowds lingering around the South Tower memorial. The waterfall from inside the huge box falls into a pool with a square hole at its center, and water pours further down the abyss.The throwing up continues. Maria sits on the edge of one of the chairs and I learn a little about her. She worked in the medical field. Her brother died in 9/11 and her son convinced her to take the museum security job where she has learned to leave her emotions at work because every day she encounters another heartbreak.She tells of trying to help a young man, sobbing in front of one of the displays, a group of drawings of the Twin Towers made by traumatized area school children. He was with several friends, who were clearly uncomfortable with his display of emotion. She asked him if he had lost a family member but he shook his head. He pointed to one of the drawings. "I drew that in 5th grade," he said. We both had tears in our eyes.Maria also tells of the many wonderful things she sees every day. The humanity, the compassion. She is reminded of the strength of the city and it's people on a daily basis, is humbled by the thousands of people who visit the museum every day, to pay their respects, learn, understand. I begin to see the crowds as less ghoulish and more compassionate.Later, Carter finds his way to the couch and sleeps. I eat a sandwich. Another security guard offers to take me to the wall to see Arron's name. Maria insists I go while she stays with Carter.I learn that Bobby, my escort, is a retired New York City Police officer. He took the job for many of the same reasons as Maria. "I lost 30 friends and colleagues that day," he says. "It's my way of giving back." I wonder how many on staff at the museum work for this same reason. A form of healing, assuaging the survivor's guilt that so many survivors must feel.We find our way to Arron's section, N21. Almost 22, our shared birthdate. His name is centered between the two people who joined him at the conference that morning. The two people he hired only weeks before. It is strange to stand there, looking into an acre-sized square hole filled with water, a giant grave. The impossibility of it all hits me again. Bobby explains how people are surprised by how far apart the two buildings actually were. "People assume they were very close since it looks that way on TV," he says.Carter is still sleeping when I return and Maria asks if I want to go downstairs. I have been glad to have Carter as an excuse not to go. "My boss will accompany you," she says gently. I am torn. I don't want to go, but feel I should, somehow. Am I strong enough? Is there any benefit? I wanted to see the museum with Carter, not a stranger, even a very kind stranger. Maria gently pushes me and I agree to go.My new escort Claudio is a retired NYPD Lieutenant. He drove to Ground Zero that morning, positioned at the head of his fleet of motorcycles and commandeered hundreds of busses to evacuate people from the area. He didn't stop working for 42 days. We descend into the gloom and he points out things as we walk quickly past them, ducking in front of people gazing at the displays. Much of the info I already know, and we breeze along so quickly, I don't look closely at much. The pit under the North Tower memorial I remember from the one-year anniversary when we were corraled down the ramp into it. The slurry wall is like a vast sculpture with its giant bolts poking from it in regular intervals. Claudio tells me that during hurricane Sandy, the pit filled with 9 feet of water. "You can see the watermark there, on the steel girder. That was the last one they extricated from the site." The girder is covered in flags and graffiti and names, the lower ones blurred where they had been underwater. The amount of water that must have flooded the area is unfathomable.Claudio shows me how to find Arron's name on a touchscreen, and make it appear in the small theater nearby. I am sorry that I have never recorded something to go along with Arron's profile. I wish there are other photos of him as well, but at the time they were collecting such things, I wanted nothing to do with this place. I didn't want Arron there either. Now it seems a shame.I am fascinated by the display of the time lapse radar imaging of all the US flights that day. At 8am, the little yellow planes that scurry around the US map look like a swarm of bees slowly dying as the lapse continues through the day and the planes are grounded.Claudio's stops by a display showing the view of the burning towers from the space station which just happened to be flying over New York at the time of the attack. Even on satellite, it's possible to see the billows of smoke. He shakes his head, "they just happened to be flying right over at exactly that time," he says. "What were the chances of that?"On our way out, we pass a huge photo of one of the towers taken from someone standing on the ground looking up. Although the display is below ground, sunlight from a window above casts a prism of rainbow on it, that lines up perfectly with the angle of the side of the building. Now nearing 4pm, I rouse Carter. He is slow to wake up, but it has been a few hours since his last episode. I am hopeful that we can make it back to the Port Authority and carry on t0 Philadelphia. It seems necessary to get Carter out of the building and out of the city."I just want to see Daddy's name," he says. I look for Maria to say goodbye. "She's on her break. She refused to take one all day," another officer tells me. Once again I am humbled by the care of people in this city and the kindness they have always shown us.At N21, Carter breaks down into sobs once again and I stand feeling tiny under his 6'3" frame, long arms draped over my shoulders."I'm so sorry," I say. There are no words.Somehow managing to conceal himself within his hoodie, he takes a photo of his father's name.At the Port Authority, Carter leaves one final parting shot, his own form of commentary. We emerge from the Lincoln tunnel as if from Hades, into blinding sunlight, and drive south, happy to be heading in another direction.

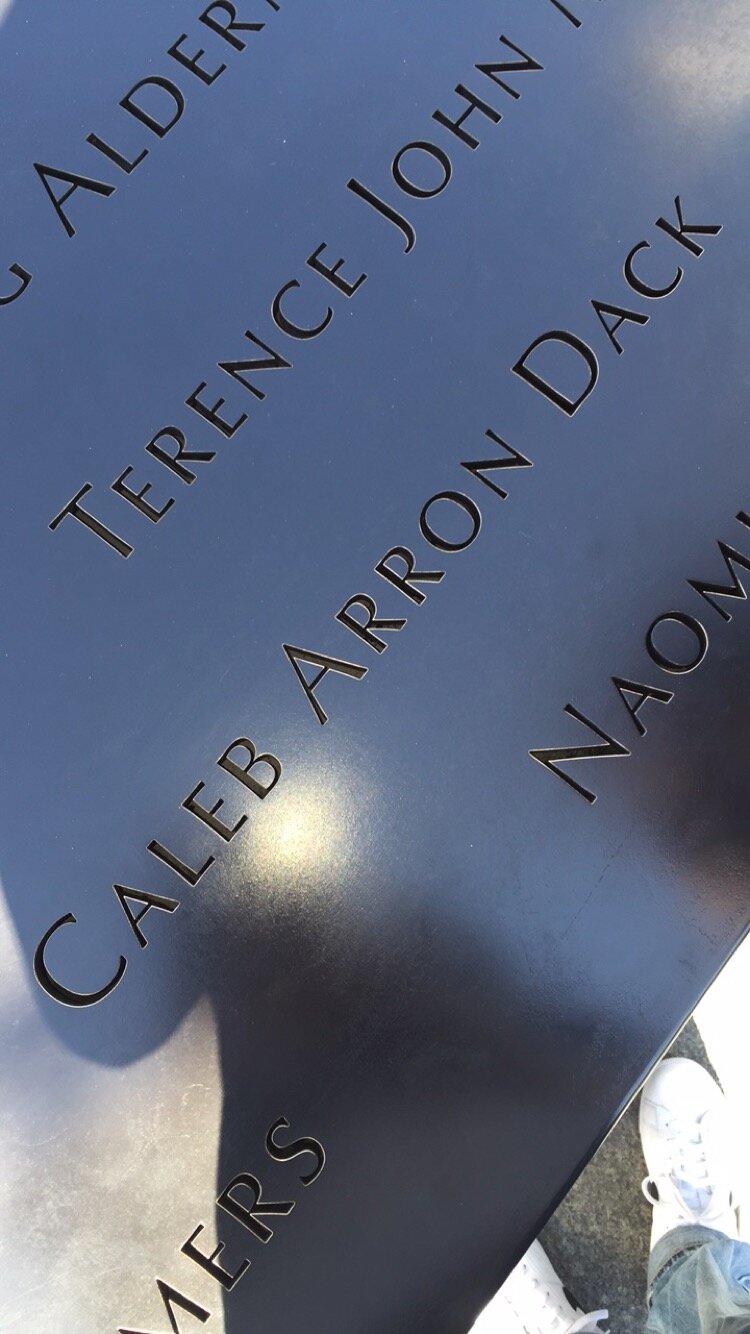

Now nearing 4pm, I rouse Carter. He is slow to wake up, but it has been a few hours since his last episode. I am hopeful that we can make it back to the Port Authority and carry on t0 Philadelphia. It seems necessary to get Carter out of the building and out of the city."I just want to see Daddy's name," he says. I look for Maria to say goodbye. "She's on her break. She refused to take one all day," another officer tells me. Once again I am humbled by the care of people in this city and the kindness they have always shown us.At N21, Carter breaks down into sobs once again and I stand feeling tiny under his 6'3" frame, long arms draped over my shoulders."I'm so sorry," I say. There are no words.Somehow managing to conceal himself within his hoodie, he takes a photo of his father's name.At the Port Authority, Carter leaves one final parting shot, his own form of commentary. We emerge from the Lincoln tunnel as if from Hades, into blinding sunlight, and drive south, happy to be heading in another direction.